From Displacement to Return: How SRAD Shaped Jordan’s Refugee Policy and Syrians’ Path Home

A Syrian refugee family crosses into Jordan, at the Hadalat border crossing. Source: Financial Times, Google Image

by: Rasha Istaiteyeh - Hashemite University

In a world where more than half of the Syrian refugees are denied the most basic means of employment, Jordan pioneered a new approach. Instead of leaving the Syrian refugees in perpetual waiting, the country undertook a carefully planned approach: to empower Syrians during their displacement so that they would one day be able to return to Syria not as victims, but as skilled and self-reliant assets. Unlike other host countries that have struggled to integrate Syrian refugees into their formal labor market (or completely omit them)-Jordan took steps in the right direction early on. Jordan provided access to work permits to the Syrians, removed the fees levied on the permits, and provided vocational training and skills development opportunities. However, it was more than a step of goodwill, it was a proactive policy crafted with a single goal in mind: to enable the person to return.

Empowerment as a Bridge to Return

Different from the model of forced permanence or temporary charity, Jordan’s strategy framed exile as a period: not a place to stay forever. By allowing access to work, contribution, and growth during their stay in Jordan, the country’s facilitation made possible a return that was intended to be much more than symbolic. It would be constructive.

Indeed, some Syrians have started to return, Even before the fall of the Assad regime . The reasons are multifaceted: economic strain in Jordan, less international aid, the lure of home, or waning belief in long-term resettlement or regime change. Whatever the case, for those who do return, the skills they acquired in Jordan may very well be the only factors determining whether they can successfully integrate or become increasingly vulnerable.

About SRAD

In response to the Syrian refugee crisis, the Syrian Refugee Camp Affairs Department was established on January 13, 2013, by a Prime Ministerial decision to manage refugee matters in Jordan. Reporting to the Ministry of Interior, it initially focused on refugee affairs within camps. On March 26, 2014, its mandate expanded, and the department was renamed the Directorate of Syrian Refugee Affairs, broadening its role to encompass all Syrian refugees across the Kingdom, not just those in camps. The Directorate's current headquarters in Shafa Badran was inaugurated on October 25, 2020, by former Minister of Interior Tawfiq Al-Halalmeh, in the presence of Major General Hussein Al-Hawatmeh, Director of Public Security.

The Syrian Refugee Affairs Directorate (SRAD) of Jordan is centrally engaged in the issue of the return of Syrian refugees from Jordan to Syria. Here is how the connection works.

Institutional Coordination and Oversight: SRAD is the lead Jordanian government agency tasked with Syrian refugee affairs, answering to the Ministry of Interior. SRAD handles administrative, legal, and security issues of Syrian refugees in Jordan. In returns, SRAD Coordinates with UNHCR and other international actors on voluntary repatriation programs. It ensures compatibility of returns with national security interests of Jordan and due processes are in place, and monitors border mobility, especially along official return routes, such as the Jaber-Nassib border crossing.

Gatekeeper of "Voluntary" Return Procedures: Even though the returns are termed voluntary, SRAD's role takes a key role in registering persons desiring to return to Syria. Also in organizing the granting of exit permits or return authorization. In addition to documenting refugee identities, confirming legal status, and sometimes flagging people for security purposes, and hence SRAD serves as a filtering process, deciding who returns and who does not on the basis of several parameters.

Engagement with International Frameworks: SRAD operates at the interstices between Jordanian sovereignty and international humanitarian norms. Therefore, it engages with UNHCR in the context of the Tripartite Agreement (Jordan-UNHCR-Syria) for facilitating returns. Participates in consultations on return issues with donor countries, typically during Amman-based interagency coordination meetings or Brussels Conferences.

Political and Practical Considerations: Jordan has reaffirmed over and over that returns must be safe, voluntary, and dignified—but pragmatically, SRAD's function may also reflect Jordan's shifting political stance. That is, in times, SRAD has allowed for small-scale return movements, particularly when Jordan is under economic pressure or undergoes shifts in foreign affairs. SRAD can also be a reflection of the government's willingness to alleviate the burden of refugees, but without sacrificing international standards. SRAD is the Jordanian institution responsible for implementing, managing, and controlling the return of Syrian refugees. SRAD serves a dual function as gatekeeper and coordinator, balancing security, legal, humanitarian, and political interests in refugee returns.

SRAD: A Policy of Pre-Planned Integration: In contrast to Lebanon’s vague ‘guest’ doctrine or Turkey’s emergency scope, Jordan has established a full-fledged, state-sponsored mechanism to autonomously govern the multifaceted policies pertaining to refugees; not just for security and humanitarian assistance, but also in terms of developmental governance for their future mobility.

Through SRAD, Jordan has created pathways to the legal labor market within agriculture, construction, and manufacturing, the very industries vital for Syria’s post-war rebuilding. It has also enabled international aid and investment through the Jordan Compact, which turned the employment of refugees into an economic asset. SRAD has Provided protecting without diverging sovereignty, thus steering clear from the region’s disjointed, foreign-controlled refugee policies fraught with opportunities for abuse. Eventually, SRAD, established human resources that could later be absorbed into Syria’s economy when conditions permitted.

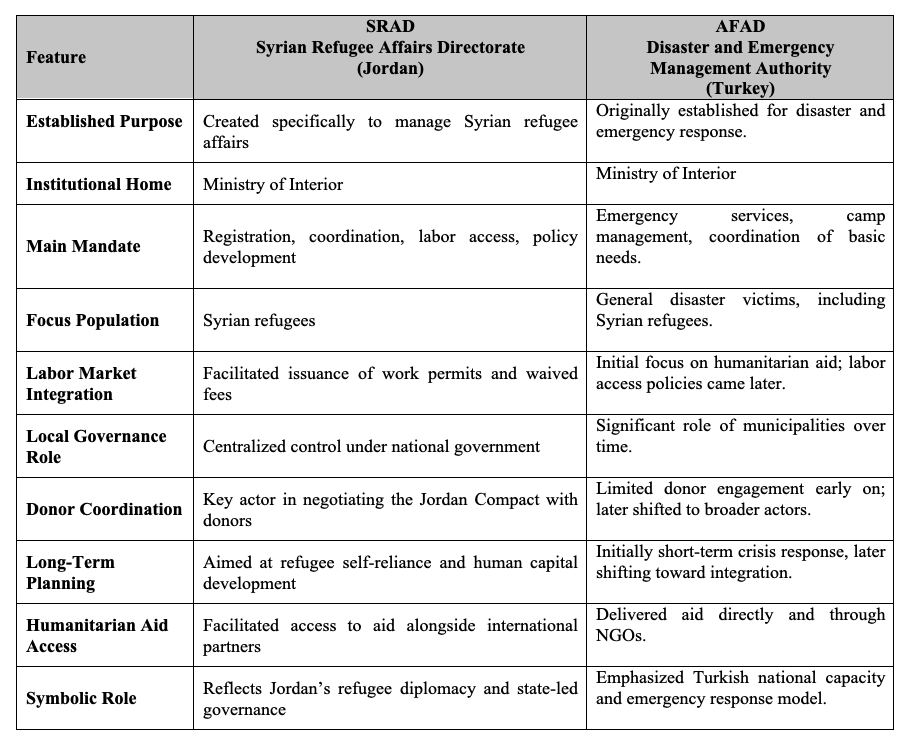

Table1. Comparison of SRAD (Jordan) with AFAD (Turkey)

Sources: AFAD (Disaster and Emergency Management Authority). (n.d.). About us. AFAD: https://en.afad.gov.tr/about-us#

Public Security Directorate (PSD). (n.d.). Syrian Refugee Affairs Directorate. Public Security Directorate https://rb.gy/wwnwuy

Jordan did not craft a policy of indiscriminate hospitality. Instead, it formulated a plan of strategy.

While there have been some states within the region who have grappled with accommodating Syrian refugee groups that are significant in number, institutionally they have been decidedly different. Jordan's establishment of the Syrian Refugee Affairs Directorate (SRAD) embodies a novel state-driven approach to governance in which governing refugees systematically figures as an extension of national mechanisms. Conversely, Turkey's response—led by the Disaster and Emergency Management Authority (AFAD)—initiated from more short-term-focused emergency aid.

Table 1 presents a comparative overview of SRAD and AFAD, showing the different philosophies and policy trajectories of Jordan and Turkey. What sets SRAD apart is not merely its administrative structure, but its mandate to enable labor access, negotiate donors, and promote long-term refugee self-sufficiency. Contrary to AFAD model of reaction, SRAD is a proactive, developmental model of refugee management-aligning humanitarian action with economic planning and national security.

This institutional variation explains the ways in which Jordan's response to refugees has facilitated the gradual shift from crisis management to labor integration and even preparedness for return. The table highlights SRAD as an innovation in refugee policy-not merely in Jordan, but within the Middle East in general.

Return as a Policy Horizon

Jordan's refugee diplomacy has always been pragmatic. It did not offer Syrians a path to citizenship, or permanent resettlement. But it offered them something: the chance to live in dignity while in displacement, and to return strong when the time comes. To that extent, return was always within limits-it was the tacit horizon. And now that circumstances slowly change and individual returns begin to happen, Jordan's approach could be humane, but more importantly, foresighted.

Jordan's model holds valuable lessons for the displacement situations of the future. It shows that refugee management can not only mitigate crisis, but also invest in the future of individuals. By mainstreaming refugee policies into national systems, aligning humanitarian objectives with economic needs, and treating exile as a stage and not an endpoint, Jordan created the conditions for a new kind of return, one that isn't coercive, but strong, and maybe transformative.

Contact:

Rasha Istaiteyeh, Hashemite University, Jordan | ristaiteyeh@hu.edu.jo